no. 13 — Reclaiming discovery from the algorithms

why they’re broken and how enterprising minds are already adapting around them

Beware: this is a long post. (I’m biased, but I think it’s worth it.)

The recent discourse around our algorithm-induced social condition has been pretty bleak – we’re trapped in echo chambers, culture has come to a standstill, and ‘enshittification’ is inevitable. Or in Kyle Chayka’s words, “the internet isn't fun anymore.”

Kyle’s latest book, Filterworld, is the first extensive report on the rise and force of algorithmic tech, but its central tenets read familiar: the major social platforms have stunted creativity, their recommendations were doomed to disappoint at scale, and social media is becoming more media, less social.

I’ll be the first to argue that algorithmic recommendations are “broken” (more on why below), but so much of the discussion to-date has taken a tone of resignation from the current world order. And yet I don’t buy that we’ve simply given up; in many cases, we’re on a more fervent hunt for inspiration than ever before.

As consumer production grows at an exponential rate, we’re increasingly turning to close friends and experts we trust to cut through the noise for us, and we’re often leveraging tech to fuel the search. This post looks at how discovery has been evolving around the algorithms that failed us, and how some enterprising minds are already capitalizing on the appreciating value of taste.

In fact, I’d argue an emerging class of creators and consumer brands is actually employing curation as a business strategy. Gohar World, Ganni and Soeur have been sharing city travel guides, Ghia has been sharing Spotify playlists, and tastemakers like Olympia Gayot and Alex Eagle are joining entirely new social platforms purpose-built for discovery and recommendation sharing. By making recommendations that are not directly monetized, these brands are building credibility, establishing a distinct point of view, and associating themselves with a whole lifestyle built around their core product (which also paves the way for category expansion down the road). They’re among what I’ve started calling the new curators of culture.

But first, let’s agree we’ve officially hit peak everything.

Replace the chrome coupes, croquembouches and bows with whatever you can’t seem to escape in your feed, and you get my point.

I’ve always been fascinated by discovery, and particularly within creative categories that have infinite repertoires – i.e., where there’s a steady stream of new production alongside inventory that doesn’t expire (think: books, wine, film, fashion, art). Here something from 20 or 50 years ago could hypothetically be just as appealing as something that launched today. So it felt tragic to see “for you” recommendations that consistently felt wrong, redundant, or were simply, trending.

My frustration triggered a lot of research into why algorithms direct us into the so-called “sea of sameness,” and here are a few of my hot takes:

The algorithm isn’t that smart.

Put simply, “for you” feeds serve up content deemed relevant based on engagement indicators from you and those it infers as your network. But the algorithm is only as smart as the data it’s fed, and it’s typically relying on a finite set of false indicators. It can’t discern between the content you watch / follow out of curiosity, professional research or boredom from the content you actually like. (Spend a minute looking up baby shower gift ideas as a woman in your 30s, and you’re getting Hatch ads for the next six years.) And with overall drops in consumer engagement, algorithms are increasingly relying on passive rather than active indicators of interest. (Gartner estimates 50% of users will abandon or significantly limit their interactions with social media in the next two years.) So if you’re not actively liking and following content, it’s forced to take cues from influencers you follow, your network, or similar demographics at large… meaning your “for you” is hardly personalized.

90% of social media users are lurkers.

How often do you check a restaurant’s Google or Yelp reviews?... And when was the last time you published one?... Studies show there’s consistently a wide supply / demand imbalance across online communities known as the 1% rule, or the 90-9-1 rule, which suggests that 90% of users are typically lurkers who never contribute, 9% of users contribute occasionally, while 1% of users account for nearly all of the content. The evolution of social media platforms into media companies with heavy video content just expands the category of lurkers who consume content without interacting with it, further warping algorithmic inputs.

Social media platforms take a blockbuster strategy approach to monetization.

The early social media days were all rainbows and butterflies, and social was presumably democratizing access to everything. WIRED’s Chris Anderson wrote a seminal piece about this in 2004, claiming the time had finally come for the Long Tail of niche content that would be surfaced by recommendation algorithms. HBS Professor Anita Elberse (and yes I took her class) said the opposite proved to be case; the tail became longer and flatter rather than bulking up. (Chris countered.) But this research was all done pre-2010. I’d argue the monetization models more recently assumed by social media platforms fundamentally changed the debate, and forced them to adopt the same “blockbuster strategy” of legacy media & entertainment conglomerates. Whereas legacy agencies had to place big bets on a shortlist of likely bestsellers to vie for limited shelf space, social media algorithms are doing the same while fighting for limited consumer attention. They’re inevitably compelled to surface content that has the highest potential to attract immediate attention and drive purchase volume, rather than take risks on something more subtle or unexpected.

Content creators are working for the algorithm. But social media is a shit boss.

Per the 90-9-1 rule, content creators (the 1%) are basically doing all the work for social media platforms without any formal employment contracts or job descriptions. Platforms don’t publicize how their algorithms work (and perhaps essentially so), but that’s problematic to creators making their entire living off of the platforms with limited control. Creators are forced to rely on the same data-driven metrics (the cultural currency of likes, follows, comments, saves, etc.) and, in turn, are incentivized to create content that immediately drives up those metrics. The result is often content created with an explicit intent to go viral, to be provocative rather than good, to follow known indicators of past success rather than experimentation. Exceptional content certainly exists, but for the most part the algorithms precipitate the same GRWMs and lame SEO-optimized headlines that deteriorate the experience for the other 99%.

We’ve drastically accelerated the pace and scale of information sharing, and thus, imitation.

As a general rule, the rate of change in society tends to mirror the rate of information exchange. Kyle references French sociologist Gabriel Tarde’s The Laws of Imitation, in which Tarde bemoans the “persistent sameness” (in design, products and service across large cities) that followed the rise of passenger trains in the late 1800s. As places connect, they inevitably begin to resemble each other. So it tracks that the sheer speed at which the same information is distributed and almost subliminally consumed on social media today contributes to an accelerated form of imitation, followed by an accelerated sense of saturation. (I can’t prove it yet, but I’m convinced this is happening in our use of language as well as visual content.) You hardly have time to adopt a new trend before someone claims it has peaked.

Where we’re turning for recommendations we actually trust

This is where I say, but WAIT! All hope is not lost!

Again, this isn’t about giving up on the algorithm or social media platforms entirely; it’s about acknowledging their limitations. History has proven time and time again that constraints often spark innovation, and that the roots of creativity and innovation get planted on the uncharted path. So I’m most excited by how we’ve been adapting around the algorithms to find and share inspiration in new ways.

First and foremost, we’re looking for sincere, *not sponsored* recommendations, whether from close friends – the people who know us far better than the algorithms, or from tastemakers – the critics / niche experts and curators of culture who we believe have an informed and compelling opinion on a category. (I want the recommendation you’re sharing because you just want to gift someone else the delight of discovering it for the first time.)

Close friends.

A lot of our exchange with close friends has moved offline to text, email, in-person. But it’s also occurring in carved out layers of the major social platforms – aka it’s going down in the DMs. Even Instagram’s Adam Mosseri admitted that users have moved on to direct messaging, closed friend communities, and group chats: “If you look at how teens spend their time on Instagram, they spend more time in DMs than they do in stories, and they spend more time in stories than they do in feed…Actually, at one point a couple years ago, I think I put the entire stories team on messaging.”

Instagram’s Q&A feature has also been blowing up lately, another example of how we’re building new roads for hunting down the good stuff.

Tastemakers.

The idea of zigging when the world is zagging is a central paradigm behind creative and business innovation. When Instagram, Pinterest, Spotify, etc. put a much wider range of information at everyone’s fingertips, they also raised the bar on what it takes to uncover something different and unexpected.

Picasso once said, “Computers are boring. They just tell you the answers.” But my response is that we just need to ask better questions. True tastemakers — the creatives and experts among us — are working much harder with the algorithms than the status quo.

Practically speaking, they’re proactively using search to get differentiated results; they’re providing different inputs to get better outputs. Maggie Mustaklem runs workshops with creatives who want to reconfigure their discovery process and stay ahead of the curve. One of her tactics is to search for the same result in a different language – e.g., “clásica villa española” vs “traditional Spanish villa”; “text to image is pretty anglophone dominant, so there are little methods you could use to counter the agency of these platforms.”

It’s pattern recognition. It’s about building an understanding around how the algorithms work and then using it to your advantage. Sometimes I’ll search “natural wine” in a new city as a hack to find a style of cute wine bars or restaurants I might like. My sister-in-law says she searches “flat white” to find the cafes in Northern Ireland that actually serve really good coffee.

We rely on tastemakers because we implicitly trust they’ll put in work to cut through the noise and curate unique content. And they’ve built extensive contextual knowledge that enables them to do this better than the rest of us.

is a case in point. She shares these monthly mood boards that I love, and the description below of how she developed her Tomatoes board shows what it took to get there. Do you just want Page 1 image search results for “tomato,” or this?

It takes a ton of practice, though, because there is SO MUCH (pre-curated) STUFF out there to consume. I started doing these little exercises for the purpose of training myself to take a step further and to think about a theme from different angles. With tomatoes, for instance, I considered a few things: their shape, their color, their translucent insides, their texture, their taste, and their many forms (juice! sauce! ketchup!) I knew that Rei Kawakubo had designed some round, architectural pieces for Comme Des Garçons in the ‘90s, so I looked through runway shots for something that might structurally resemble a tomato. I remembered that I had some boots saved to my wishlist from Charlotte Stone made in this sort of half-glossy, tomato red leather. I thought about the proportion of color on a classic tomato: mostly red with a little bit of green. It’s a balance between being too abstract that it no longer is about a tomato at all and too on-the-nose, where it’s just a bunch of photos and drawings of tomatoes. — Notes of: Tomatoes

Curators of Culture.

Relying on creatives or niche experts (e.g., wine or book editors) is not a novel concept, though I do think we’re leaning on them more heavily as an antidote to algorithmic recommendations, and I know they’re working harder to produce differentiated suggestions.

But I’d argue a couple factors, in particular, are also facilitating an entirely new class of cross-disciplinary tastemakers—or curators of culture—who we’re looking to for all of their lifestyle recs rather than recs confined to their areas of domain expertise.

First, we’re encountering a larger fusing of cultural and creative boundaries than we have historically. The fluidity between food and art, fashion and music, fashion and sport has been especially salient (consider: Pharrell as Louis Vuitton’s Creative Director, luxury brands betting big on tennis). So we’re more naturally open to considering a tastemaker’s recommendations across adjacent categories.

Second, I’m reflecting on a point former Netscape CEO Jim Barksdale famously made in 1995: “There are only two ways to make money in business: bundling and unbundling.” I think we’re burnt out by the fragmentation that the D2C era brought to everything. After subscribing to tons of hyper-niche content over the years, the idea of a couple brands we really love giving us a free bundled set of general lifestyle recs sounds like a dream. So yes, I want the A24 cookbook. Of course I’m curious where Laila Gohar went in Kyoto. Sure, I’ll see what’s up on Ghia’s OOO playlist.

Obviously, not every brand can be a lifestyle brand or be valued as a curator of culture. Like any business strategy, it requires successful execution and some agility.

While some of these individuals and brands are sharing their cultural recs on Instagram, many are keeping them confined to more expressly opted-in CRM subscribers. Gohar World had this IYKYK drop called Studio Lunch, where they would text you a super simple recipe the team was making for lunch in the office that week. (I think they wound it down last year, but it was fun. And it works for as long as it feels original.)

Others have joined entirely new social recommendation platforms: most notably, amiGo, which has signed up the likes of Olympia Gayot, Sam Youkilis and Maryam Nassir Zadeh.

But will the new platforms get enshittified too? Depends on how they monetize.

With the wave of discovery platforms coming to life, let’s not forget that many more died in years prior. Why? Can’t explain it better than Cory Doctorow:

Here is how platforms die: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die. I call this enshittification, and it is a seemingly inevitable consequence arising from the combination of the ease of changing how a platform allocates value, combined with the nature of a "two sided market", where a platform sits between buyers and sellers, hold each hostage to the other, raking off an ever-larger share of the value that passes between them.

So we’re left to wonder whether newer platforms will face the same fate.

I’ve tested a lot of these products myself and spoken with the founders of most. Some have even grown a sizable following: Letterboxd had 11M users in 2023 (would love to get the post Ayo Edibiri-effect figure tho). There are a few I enjoy using, and an even smaller number that I believe are thoughtfully avoiding enshittification traps.

In light of the Google Maps world I live in below, I’ll just flag some of the newer travel / restaurant recommendation platforms I’ve looked at to start: amiGo, Step, PI.FYI, Beli, It’s Good.

DM me if you want a real deep dive on this space, but it’s hard to place bets until these platforms establish sustainable monetization strategies. (History suggests freemium subscriptions have worked the best, transactional models the worst.)

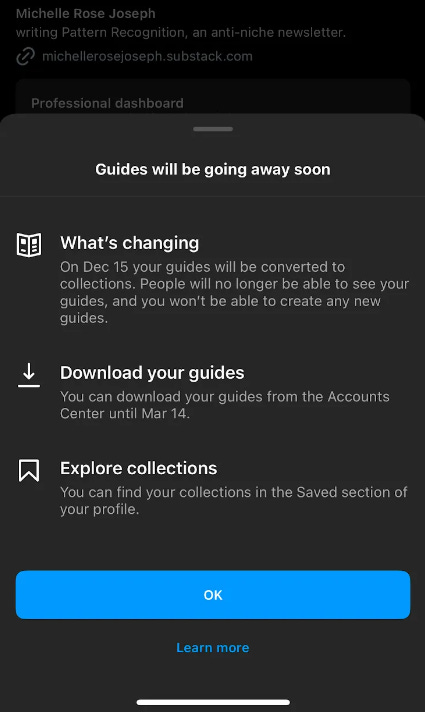

On a product level, I find Beli interesting because it’s one of the first to address the underlying supply/demand imbalance on social. Beli essentially requires users to rate (lurkers beware) and force rank (controversial but effective) restaurants in a low friction way that ultimately informs far more accurately personalized recommendations. A “come for the tool, stay for the network” strategy. (Also editors, hmu if you want my story on “The Irish exit of Instagram guides”...)

Substack has been one of the most natural homes for our evolving discovery and recommendation culture. The Times alluded to this last summer, when discussing the rise of former fashion editors and journalists on the platform (

, now). But as a writer on the platform myself, I’m really torn on what will come of it. On one hand, I’m watching the moves by the product team that feel like thoughtful attempts to row against the current (e.g., new language and local payment options to encourage cross-cultural readership, pushing the recommend other writers feature which has called “one of the most impactful growth features in history”). Writing longform content also takes a hell of a lot of work, which creates some barriers to entry that hopefully preserve the quality and individuality of content on the platform.But on the other hand, as more writers strive to make a living here, Substack remains susceptible to the same affiliate link and “working for the algorithm” corruption as the other social platforms before it. It’s also not lost on me that longform content doesn’t work en masse. As more creators I enjoy in other formats start joining and sharing longform essays on substack, I won’t be able to read or support them all, even if I want to. So I think readers are going to become far more selective about what we subscribe to. But I hope the happy outcome is landing at a place where the fan-to-follower ratio moves closer to 1.

A taste of part 2.

It felt remiss to end a post on recommendations and tastemakers without actually contemplating taste.

Philosophers have debated this for centuries, but my own verdict is that our taste-based preferences are a matter of individual and subjective opinion. So what ultimately qualifies an individual’s taste as good or bad is not some objective measure of what we’re evaluating but rather that the rubric we’re using is defined and consistent. Like other opinions, I believe taste should be evaluated based on the structural integrity of the judgment that informs it.

This is more relevant than ever because the access social media provides to what others “like” makes it far too easy to subscribe to the same things and to avoid acknowledging why we may actually prefer others. I think we’re turning to our close friends and tastemakers in part because we’ve lost touch with our own taste rubrics. We buy things impulsively and then wonder whether we ever liked them.

Lately I’ve been placing a premium on distinct, defined points of view. In fashion, I’m drawn to individuals who seem to dress differently but with intention:

, Iris Apfel, Blanca Miró, Sarah-Linh Tran. Their style feels oblivious to the algorithm but also internally consistent; it’s not different for the sake of being so, just defiantly authentic to their own taste.Ultimately, I think taste is an argument. And I’m most moved by recommendations that challenge me to debate my own position, whereas the algorithm is designed to reinforce it.

Stay tuned for a part 2 focused on staying inspired and refining your own taste in today’s Filterworld.

Postscript

Re: no. 11 on my love-hate relationship with travel content – J. Crew just did a shoot at Hotel Corazon.

Re: no. 12 on The Lineup – the team just released the deets for season 3. Check it out. Also

’s food reviews on Taste have a way of making you lol and also pause pensively (see Horses), so I’m interested to see what he’ll do with the rebirth of his substack.Re: no. 8 on restaurants & democracy – The world ripped into Wendy’s “dynamic pricing” announcement after interpreting it as surge pricing. And the New Yorker wrote about why NYC restaurants are going members-only.

Re: NY’s best all day cafés – Couldn’t include Oxalis’ new all-day café concept in my edit because it hasn’t opened yet. But it’s opening in April, and I can’t wait. And now we know they’re also opening Laurel Bakery in Cobble Hill at the same time “which will serve as the breadbasket for our sister restaurants” (so Otway will be getting tapped out at PDF).

Re: no. 10 on the creative directors’ bible – Rick Rubin designed a web template you can use on Squarespace as part of the Squarespace Icons project. I found the narrative more compelling than the template itself.

Thank you for shifting this conversation from resignation to creative adaptation and curiosity-driven choices!

Thanks for writing such a great post on this topic. I've only tangentially touched on this but have not stopped thinking about it since reading Filterworld. I mean, I knew this existed, but didn't realize the impact. I now go out of my way to find things in dark corners, through friends, through search, and actively seek out people to give me recs vs just scrolling around on social. Word of mouth is still such a powerful tool even in this algorithmic age.