If you’ve landed on creative director tok in the past year, you’ve probably been recommended Rick Rubin’s The Creative Act: A Creative Way of Being.

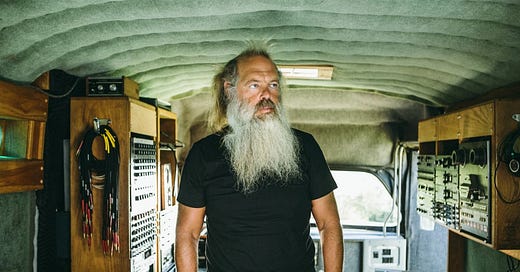

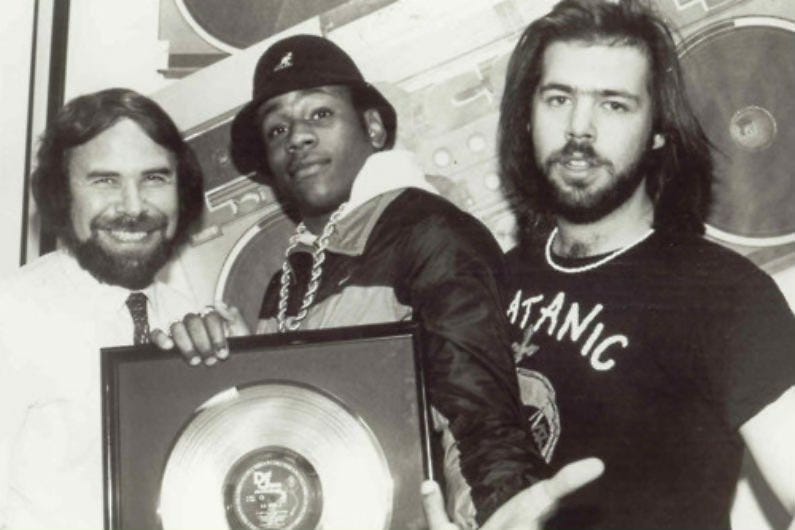

Rick Rubin is, quite objectively, a music genius. He’s a nine-time GRAMMY-winning producer, co-founder of Def Jam Recordings, founder of American Recordings, and former co-president of Columbia Records. He was also among Time’s 100 Most Influential People in 2007.

Rubin played an essential role in defining hip hop as a genre, having produced records for the Beastie Boys, LL Cool J, and Run-DMC. But he also has a range like no other: his credits include collaborations with the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Tom Petty, Adele, Eminem, AC/DC, Kanye, Josh Groban, Mick Jagger, Jay Z, Slipknot, Lady Gaga, U2, Johnny Cash… the list goes on.

But Rubin refused to write the tell-all memoir that publishers fantasized about. In fact, his initial pitch 8 years ago was rejected by every publisher he met, but he wrote the book anyway. He went back to publishers once he had a complete 400+ page draft, and it quickly went on to become a #1 NYT bestseller.

And that in itself illustrates the core message of his manifesto: The best shot you have of producing work that resonates with the world is by not caring what it thinks. People connect with a work’s honesty and authenticity at a fundamental level.

“I set out to write a book about what to do to make a great work of art,” Rubin shares, “instead, it revealed itself to be a book on how to be.”

The TLDR

Frankly The Creative Act is a bit cerebral (I mean, Rubin wanders around Shangri-La barefoot to feel more connected to the universe…), so it probably isn’t a quick add-to-cart for everyone. But the purpose of this newsletter is to unpack what shapes society by looking across a broad range of people, industries, and creative mediums. And I hope it introduces you to ideas you might not have otherwise considered. So I’ll give you my TLDR recap of the book, along with some extended reflections to read at your discretion.

Overall, I found the book provocative in its sincerity and humility. Rubin makes no authoritative claims on creativity (he opens by saying “Nothing in this book is known to be true”), but so many of his points resonate with how I’ve thought about Pattern Recognition — both as a body of writing and as a philosophy around the shared sensibilities of creatives and entrepreneurs. (And any other Founders podcast fans will recognize Rubin’s artistic approach as being consistent with that of many legendary founders throughout history, as I’ll draw out below.)

I was shocked to learn Rick Rubin doesn’t play a single instrument, and he has said he knows nothing about music. So if his real “genius” is in figuring out how to understand his own instincts and unlock the potential of individuals he works with, there’s probably something in here for artists and entrepreneurs alike?

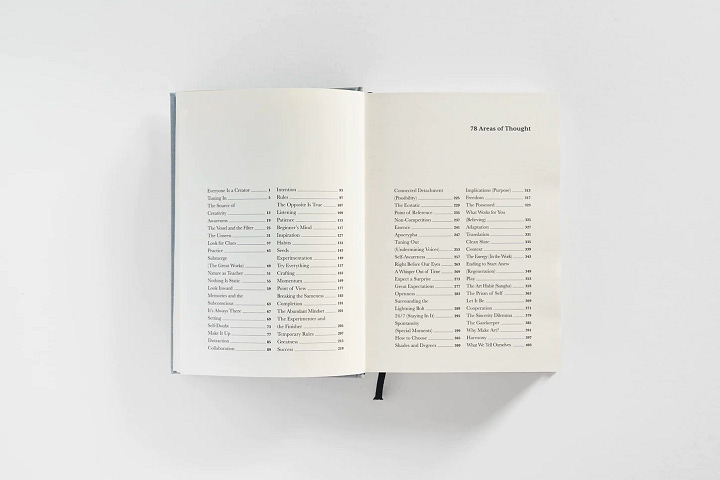

The book isn’t written sequentially, but Rubin’s 78 musings coalesce around three major areas:

Artistic sensibilities. Rubin believes a spirit of rule-breaking underlies creativity. He refers to art as a practice of paying attention and invites artists to tap into their childlike “beginner’s mind” to challenge assumptions and consider a world of infinite creative possibilities. (I found these ideas easiest to subscribe to because they align with my theory that an ability to identify patterns and then subvert or recontextualize them sits at the root of creativity and innovation.)

The creative process. Rubin believes inspiration is on a “cosmic timetable” and as unpredictable as the arrival of waves in the ocean. The artist’s obligation is to be ready, ride each wave for as long as possible, and then be ready to anticipate the next. He speaks a lot about the importance of releasing work into the world, so you can make space to create the next.

Interpretation. “In terms of priority, inspiration comes first. You come next. The audience comes last.” Rubin believes art is fundamentally a vehicle for self-expression. So when they’re produced as pure acts of devotion to the universe, they render criticism and competition wholly irrelevant.

At its core, this book says the path to producing meaningful work begins with practicing the life of an artist.

Upon further reflection

Read on if you want to dive further into the book and my reactions, or read the first poem I’ve written since high school…

Artistic sensibilities

01 - Refining a childlike sensitivity

Rubin says creativity is the art of paying attention, being attuned to clues without jumping to conclusions. We should aspire towards detached observation, and specifically look for the things we notice but no one else sees.

When clues present themselves, it can sometimes feel like the delicate mechanism of a clock at work. As if the universe is nudging you with little reminders that it’s on your side and wants to provide everything you need to complete your mission.

He offers some common wisdom: meditate, take walks in nature, connect with gratitude, keep a dream diary. But he says the purpose is not in the act themselves but to evolve the way we see the world.

The goal is to tap into a playful, childlike subconscious – an uninhibited “place of not knowing” where we’re freed from limiting beliefs (i.e., our tendencies to define, classify, and simplify according to preconceived notions). In that space, we feel free to think differently.

02 - Pattern Recognition and rule breaking

Rules direct us to average behaviors. If we’re aiming to create works that are exceptional, most rules don’t apply…Often, the most innovative ideas come from those who master the rules to such a degree that they can see past them or from those who never learned them at all.

Rubin includes some tactical advice on how to encourage rule breaking:

“breaking the sameness” change your environment, change the stakes (imagine you’re writing the last song you’ll ever write), invite an audience, change the context, alter the perspective (record with headphone volume extremely loud), write for someone else, add imagery, etc.

“temporary rules” create self-imposed constraints (e.g., George Perec wrote an entire book without using the letter e. Yves Klein only painted in blue and ended up discovering a shade no one had seen before).

“openness” actively stretch your point of view, be deeply curious about beliefs that are different from your own, and purposely experiment past the boundaries of your own taste. I completely agree with this, and it reminds me of one of the most impactful articles I’ve read, written by Janan Ganesh, one of my favorite writers of all time: How to choose your friends wisely: What enriches life is not the number of friendships nor the depth, but the range of the people you meet.

The creative process

03 - Art is on a cosmic timetable

If you have an idea you’re excited about and you don’t bring it to life, it’s not uncommon for the idea to find its voice through another maker. This isn’t because the other artist stole your idea, but because the idea’s time has come.

This might have been the most provocative idea in the book. Lately I’ve been observing content creators more aggressively staking claim over ideas they put out into the world (e.g., “as I first wrote about several months ago,” screenshotting proclaimed imitators, etc.). And I read it as so ridiculously self-absorbed… as if upon publishing an idea in any public domain, the emergence of a similar idea could only be considered a reproduction of the first.

In today’s rapidly evolving information economy, the concept of “ownership” is becoming ever more contentious. So there’s something liberating about Rubin’s premise here, which relinquishes ownership altogether. He suggests the artist is simply a vehicle for transmitting a ripe idea.

But Rubin also relays this view of the “cosmic timetable” as a word of warning: “When we miss [inspiration], it really does pass us by. Tomorrow presents another opportunity for awareness, but it’s never an opportunity for the same awareness.”

04 - The artist’s obligation

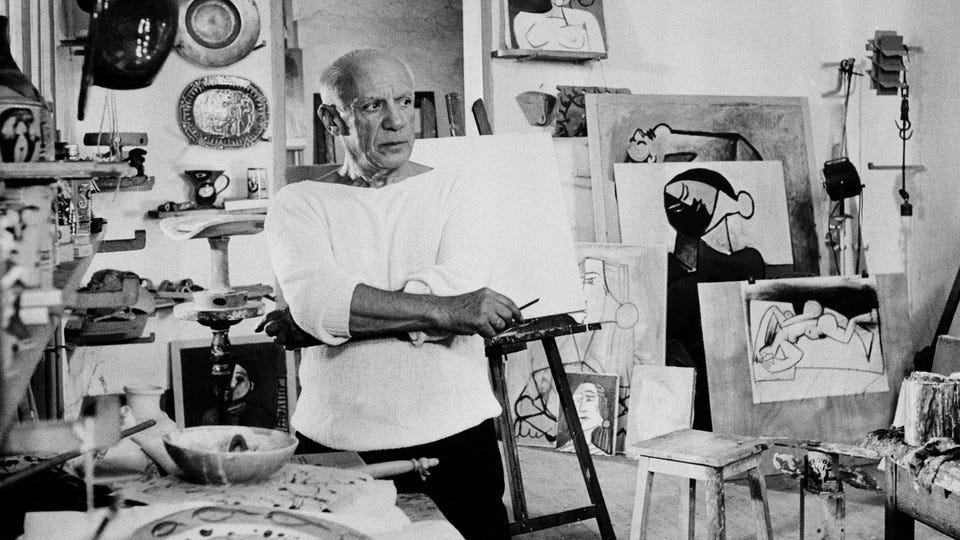

Rubin thinks of inspiration rolling in like waves; unpredictable and fleeting, so the artist has to be ready to spot it and also committed to riding the wave for as long as possible. He says, you can’t say you’re going to catch fish but you have to be out there fishing. (This reminds me of a favorite Picasso quote: “When inspiration arrives, I want it to find me working.”)

Rubin also urges artists to work as far forward as they can whenever inspiration strikes:

Remain in the energy of this rarefied moment for as long as it lasts. When flowing, keep going…Our schedules are set aside when these fleeting moments of illumination come…This is the serious artist’s obligation…If we step away and let that initial spark fade, we may return to find it’s not so easy to rekindle. Think of inspiration as a force not immune to the laws of entropy.

This means always push forward to a full draft. If you’re stuck, just move on and the rest will reveal itself. He offers a helpful analogy: if you’re holding a center puzzle piece against an empty tabletop, you won’t know where to start. But once you complete the rest of the puzzle, you’ll know exactly where it goes.

05 - Volume and experimentation

In creating art, Rubin says you should try everything. Collect seeds of ideas and focus on flourishing them before pruning. Generate possibilities instead of eliminating them, so you can leave room for the unexpected to happen. (Countless inventions were discovered by accident, after all.)

Push to publish. Don’t be precious about it. Lower the stakes and think of completing each work as a stepping stone to the following. He says, “hanging on to your work is like spending years writing the same entry in a diary.”

While the artist’s goal is greatness, it’s also to move forward. In service to the next project, we finish the current one. In service to the current project, we finish it so it can be set free into the world.

Rubin also refers to “the abundant mindset,” suggesting that “when we share our works and ideas, they are replenished.”

Maybe he’s right. The idea of being prolific is one I’ve found recurs frequently in the Founders podcast series, where Brian Senra studies the lives of 1000 of the world’s greatest entrepreneurs. Picasso averaged one new piece of artwork every day of his life from age 20 until his death at age 91; he created something new every day for 71 years. Balenciaga sewed every single day for more than 70 years. Mozart composed over 600 pieces in his lifetime. And naturally, putting each new piece out into the world creates an additional opportunity for it to reverberate.

06 - On work and refinement

Rubin’s advice for directing the production of art is to follow what he calls “the ecstatic.” These are the feelings that serve as an inner compass and could include a sense of awe or delight that might accompany a minor tweak in the work. This is one of the most abstract points of the book, but I think I get it. And LL Cool J says he gets it; he feels an inexplicable urge to laugh when he’s writing and nails the lyrics to a song, even when the song isn’t funny. It’s a sense of wonder.

When editing, Rubin warns against over-analyzing or rereading the same work because you’ll risk becoming attached to it. Take breaks and invite distraction when necessary to avoid attachment to conscious beliefs. The end goal is to get a work down as close as possible to its essence.

He cites a helpful quote from the French writer, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: “Perfection is finally obtained not when there is no longer anything to add, but when there’s no longer anything to take away.”

This mindset reminds me a lot of Anna Wintour’s approach to editing. She was ruthless in her devotion to avoiding excess. She was known for her terse memos, binary feedback, “AWOK” signoff, and for believing email subject lines were superfluous.

Interpretation

07 - The audience comes last.

“In terms of priority, inspiration comes first. You come next. The audience comes last.” Rubin believes the purpose of creating art is to decode and translate inspiration in a uniquely personal way:

The reason we’re alive is to express ourselves in the world. And creating art may be the most effective and beautiful method of doing so. Art goes beyond language, beyond lives. It’s a universal way to send messages between each other and through time.

The artist’s primary goal should be to produce their best, most authentic work. Critics’ opinions are irrelevant because they’re out of the artist’s control. In fact, something truly creative is often polarizing by definition. Creative marks change.

I wonder if we can think about these aspirational works of art in the same way we think of truly disruptive tech: you succeed by creating something that people didn’t even know they needed.

08 - You’re either an artist or you’re not. There’s no such thing as good.

Rubin argues that being an artist is like being a monk. You’re either living as a monk or you’re not; you can't be bad at it. In the same way, the artist’s work is the process (“a way of being”), rather than the output.

This is why he thinks the idea of competition is absurd. Rubin says the Grammys make no sense (despite having won 9 awards himself), because all art is 1 of 1.

Interestingly, Bob Iger has shared anecdotes of a “movie mastermind” network in his book The Ride of a Lifetime. Apparently George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and Quentin Tarantino would play their movies to each other before they were released to the public. They were so confident in their distinct personal styles that they were never afraid of competition.

Success occurs in the privacy of the soul. It comes in the moment you decide to release the work, before exposure to a single opinion. When you’ve done all you can to bring out the work’s greatest potential. When you’re pleased and ready to let go.

A short poem on creativity

With that in mind, I felt compelled to leave you all with something I wrote in August, before I had ever heard of Rick Rubin’s book.

Now I’d never call myself a poet. Before August 2023, I hadn’t written a poem in over 15 years, and I haven’t written another one in the four months since. But I do recall thinking a lot about the seemingly complicated relationship between artists, their work, and its consumers this summer. And I vividly remember waking up in the middle of the night one night, feeling compelled to type this into a Google Keep note on my phone. To say that was “out of character” is a serious understatement, but it happened.

I hadn’t given this note a second thought until now, but upon rereading my words, they seem to quite directly echo the central tenet of Rubin’s book. And that is completely insane to me, but I thought I’d share it and hope it resonates with whoever it’s meant to.

create to make, or to be received?

“listen to your gut”

“follow your heart”

“you’ll know in your core”

all along the central axis

and yet—

the made sits in the outer orbit

and beauty is in the eye of the beholder

a sound can fall on deaf ears

a morsel passes from your hands to their tongue. yes, chef!

so create to make, or to be received?

when we create to make, we create with purpose

and purpose is not seen nor heard nor tasted

it is felt.

felt in another’s gut

in her heart

in her core

so if we create for ourselves,

we create a portal for two souls to connect.

there we have the works that shape the world.

Sources: The Creative Act: A Creative Way of Being // Showtime docu-series Shangri-La // Jay Shetty podcast ft. Rick Rubin: Why Unconventional Methods Lead to Success & The Secret to Genuinely Love What You Do