no. 6 — Ugh the fashion industry reminds me of the US healthcare system

why digitizing our wardrobes could be the key to sustainability

I’m no routine curmudgeon, but I realized I’ve been bristling at every announcement of a fashion brand’s new sustainability initiative, just as I had whenever a healthcare provider said they were going to lower the “cost” of care.

And I say this as someone who has worked across both industries: today’s idea of “sustainability” is to fashion as “affordability” is to healthcare — a farce.

Ok hear me out…

The truth is I don’t blame the brands or the providers. They’re operating as perfectly rational actors within systems that incentivize over-production and over-consumption. I won’t even deny that their efforts have driven well-meaning improvements to the status quo. But we’re missing the main point.

Fashion’s sustainability efforts to-date have largely addressed choice of materials, distribution, and (increasingly) recirculation. But they overlook the root problem: accelerating production + declining utilization = Too. Much. Stuff. And this could be likened to healthcare affordability initiatives that focus on curtailing “costs” by capping insurance reimbursement rates. They disregard the central role that “prices” play in determining what consumers will pay out of pocket for a service.

I should point out my perspectives on the healthcare industry are heavily shaped by David Goldhill’s analysis in Catastrophic Care and the two years I spent helping him build a patient-centric marketplace solution at Sesame. While I'm in no way suggesting the purchase of apparel bears the same weight as the purchase of a health care service, I can’t help but draw WTF?! parallels across both: We have closets full of clothes but nothing to wear. We leave our doctors appointments guessing whether we’ll get a bill for hundreds of dollars or none at all.

Why? Both industries are fraught with similar systemic issues and misguided economic incentives — a ton of waste and a lack of transparency that distorts consumers’ perceptions of reality. So initiatives designed to accommodate the existing structures can only drive incremental change. I think truly sustainable fashion (and affordable health care) has to start with a better customer experience. It starts with giving consumers the data and tools to be more discerning buyers.

I love fashion, but I genuinely struggle with the relationship we have with clothing today. The industry perpetuates an impulsive binge and purge cycle. We aspire to build capsule wardrobes but we don’t know how to work around what we already own. We shop for items but live in outfits. We want investment pieces but have no idea what that means. We’ve always thought of fashion as self-expression, but it feels like the algorithms on social media are expressing a bleak, homogenous future.

I want to continue supporting the fashion industry, but I want to do it by making more deliberate purchases and with far fewer regrets. Fortunately, I think we’re also at an inflection point with the rise of a broader “reductionist” consumer mindset; shoppers want to buy “fewer, better” things and are ready to hold brands accountable to higher standards of efficiency if we’d only give them the right tools.

…Ok, I’m listening

Waste (mo money mo problems)

The US spends more on health care than any other country, with 25 - 30% of it ($760 - $935 billion) considered waste annually. This waste is generally attributed to failures in care delivery, care coordination, administrative costs, and over-treatment, but could be more succinctly explained as “our insurance system sucks.”

And while the fashion industry’s challenges with excess inventory are widely known, global production has still tripled to 150 billion garments annually over the past 20 years, with 30% of them ($500 billion in value) discarded before ever reaching point of sale. This gets compounded by the fact that our utilization of garments (how many times we wear an item before retiring it) has dropped more than 40% over the same period. I mean, the average US consumer today purchases 70 new articles of clothing each year. You don’t need a professional opinion to know that the average US consumer does not need 70 new items of clothing per year!!

Transparency (or lack thereof)

If you’re asking yourself “Why are we like this?” I’ll say most of the issues in healthcare and retail boil down to fragmented data and information asymmetry.

Health insurance is the single most expensive benefit US employers provide to their employees (they spend $1 trillion a year on it), and yet they’ve had to blindly rely on insurers to negotiate pricing on their behalf. “Just trust me on this.”

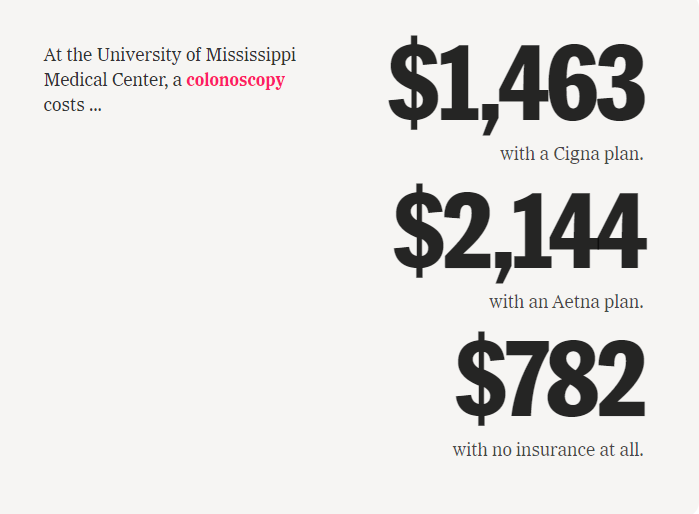

When new CMS price transparency rules went into effect in 2021, finally requiring hospitals to disclose their lists of insurer-negotiated prices, employers started asking the right questions about multi-million dollar discrepancies. And consumers started realizing that they can be better off paying in cash for a service than using insurance in the first place. Compliance has been slow moving and incomplete, but consumers are at least starting to access the information they need to hold systems accountable.

In retail world, brands have held a similar shroud over their unsold inventory figures. According to the 2023 Fashion Transparency Index, only 12% of companies disclose annual product volumes. But by some accounts, Shein (fashion’s favorite sustainability scapegoat) has been adding between 2,000 to 10,000 new styles per day, with 40% ending up as waste within a couple of weeks. Fashion councils in Europe and major trade groups in the US have been lobbying for new disclosure standards, but I think it would be more efficient and impactful to just give consumers clearer visibility into what they own. (More on why digital closets could be the answer below.)

Perception vs Reality (and math that doesn’t add up)

Our encounters with both health care and retail are notably episodic and prone to recency bias. So without access to an accurate, consolidated set of information about our prior purchases, we inevitably have skewed perceptions of reality and actual dollars spent. In user interview contexts, this can sound a lot like denial or hypocrisy, but we genuinely lack the tools to better calibrate. We default to acting intuitively rather than objectively and often make up our own math to rationalize our decisions. Did you know you need to wear an article of clothing at least 30 times before recouping its purchase value, but we only wear them 7 times on average today?

An inflection point for sustainability in fashion…

Growth of the secondhand market has been one of the defining retail developments of our time. Per the BoF + McKinsey 2023 State of Fashion Report, resale revenue will grow from $15 billion in 2022 to $47 billion in 2025 (11x faster than the broader apparel market), and the rental market will surpass $2 billion in the same time frame. In 2022, more than 1 in 2 consumers shopped secondhand in 2022, 1 in 3 apparel items purchased were secondhand, and 2 in 5 items in Gen Z’s closet were secondhand (thredUP).

But I think we’re also seeing a new, more exciting angle on sustainability gain traction — the rise of the reductionist “less is more” mentality. Take “outfit repeating,” a once cardinal sin turned new cool; the “de-influencing” trend; “no buy July” and other vows to cap purchases. It feels like there’s been more emphasis on non-branded styling (@lotte.world) and interest in learning how to evaluate “investment pieces” in our wardrobe than ever before.

In my first post, no. 1 — “Good Vibrations” and the pulse of a movement, I raised reservations around whether sustainability could take off as a veritable movement without more direct consumer participation. This feels like the turning point where consumers will become the agents and evangelists of sustainability.

WSGN, the renowned trend forecasting agency, even included the “Reductionists” as one of four emerging consumer profiles in their 2025 Future Consumer report:

“There’s a cohort of consumers now…that feels stuff as an emotional load. For this group, financial pressures and growing awareness of fashion’s environmental and ethical shortfalls have turned once pleasurable impulse buys into a weight. [There’s] guilt associated with those products now that I don’t think consumers were attuned to, even…three or five years ago.” (WSGN’s Allyson Rees in Business of Fashion)

…Aren’t a million companies already working on this?

In short, yes. A ton of companies are working on improving sustainability but mostly through resale or other models that accommodate brands’ interests ahead of consumers’. I’m no expert in this space but I highlight several key market players and some limitations with existing approaches below.

The reality is that growing resale on top of a consumerist world drives unintended consequences (e.g., the complicated ethics of thrift store ‘gentrification’). And that’s why the only way to curb fashion’s waste problem and comprehensively improve sustainability is to start by addressing what consumers already own.

A snapshot of today’s fragmented sustainability tech landscape and its limitations

P2P resale: Poshmark, TheRealReal, ThredUp, Depop, Vestiaire Collective — First movers but constant struggles with matching supply & demand, authentication, valuing vintage, etc. I’d also love to know how often secondhand is used as a supplement rather than alternative to buying new.

Cross-platform resale: Vendoo, Beni — Tools to aggregate, cross-post, or compare pricing across resale platforms.

P2P rental & exchange: Pickle, HURR Collective, Nuw (swap or lend) — Fascinating that so many of these are taking off. I worry these perpetuate the need for newness, but there’s more to unpack here re: understanding utility value in $ vs credits and product lifecycles.

Shopping Organization: Locker — Locker pitches itself as a way to organize all your shopping tabs, so it’s not a sustainability tool per se. Today, I see it as a conversion-oriented alternative to what people are already using Pinterest for. But something like this alongside a view of our existing wardrobes could be a great tool for making more intentional purchases.

B2B branded resale – Archive, Fleek, CaaStle, Treet, NOLD (hybrid P2P and branded) — Every brand feels pressured to start its own resale program, and these platforms help with that. But brands are incentivized to sell new full-priced merchandise, so it’s hard to see them meaningfully promote resale at the expense of their topline until consumers demand that they do.

Excess inventory management: Ghost, Otrium — Creating new opportunities to monetize excess inventory may initially reduce waste but ultimately feels like a hall pass for overproduction. USV-backed Ghost says it has already listed $1 billion of inventory on its platform which is pretty wild.

Recommerce: Re-Up, AirRobe, Croissant, TipTop (launched by Postmates’ founder) — These tools bring the estimated resale value of products top of mind at PoS (apparently 82% of Gen Z are already there), but they’re also designed to increase conversion at checkout so we fuel the consumption problem. And could somebody explain how these instant cash platforms don’t just turn into insurance risk modeling companies without verifying actual product condition at resale?

Digital product passports: EON — Digital ID and data architecture platforms for tracking products throughout their full useful life. This is an area to watch in light of new EU restrictions that will apply to all products placed on the EU market whether produced inside or outside the EU. (It also calls for new ”interoperability” standards, so we have yet another tie to the healthcare system!) EON is already partnered with Coach, Chloé, and Target among others.

Why digitizing our wardrobes could be the key to sustainability

At grad school we had an assignment called FIELD 3 where we launched microbusinesses. My team developed a concept called Spacement — a solution for seasonal storage that allowed you to digitally-inventory your items (think Christmas decorations, winter wardrobe, ski gear, etc.), store them off-site for most of the year, and then reclaim them on-demand. I’m pretty sure we called it “the closet in the cloud” before RTR did (lol), and our master plan included features to track how long items were stored in Spacement and list idle items on our own marketplace with ease.

We shut down Spacement after the assignment because we were young and having too much fun to pursue it, but lately I’ve been thinking about how this concept could be repurposed to solve fashion’s sustainability crisis — i.e., where it’s not just for cataloguing seasonal items but is instead a digital inventory of your entire wardrobe. The consumer-first, utilization-driven model we are looking for?!

Wouldn’t it be better for consumers to first consider and maximize what they already own before making a net new purchase? To understand how they actually utilize their clothing and start thinking about their wardrobe like a financial asset (e.g., reviewing the “cost per wear” of each item)? To bridge the current gap between perception and reality when it comes to their style and spend? To be prompted when an item hasn’t been worn in a while so they could either repurpose it or pass it on to someone else who will?

And wouldn’t this knowledge ultimately hold brands accountable to a higher standard? Challenge them to compete for consumers’ share of wallet with higher quality and more differentiated, mission-aligned products? Or to show consumers how their products could be styled in multiple ways? Wouldn’t brands get the best understanding of their customers by knowing what else they actually own?

There are a handful of new digital wardrobe apps out there — Indyx, Whering, Acloset, Stylebook, Storey. I’ve personally tested several of them, and they all have different monetization strategies and levels of product sophistication (bulk upload remains a universal challenge but not an insurmountable one).

Avery Trufelman, a brilliant fashion podcaster (of

), also profiled several in a recent episode, but her take is more pessimistic. She says there’s “a strange hex on the business model” that’s at odds with the industry, i.e., seeing your closet will ultimately make you shop less.But to me, that’s precisely the point. The most innovative ideas sound crazy until they don’t (Uber, AirBnB). Virtual closets could follow a similar pattern of disruption (at the risk of using that word), and they also have a compelling strategy for overcoming the Cold Start Problem encountered by most marketplaces. It’s the “come for the tool, stay for the network” approach. Virtual closets start by serving as a daily utility tool for users before those users ever become suppliers on its marketplace.

I’ll just leave this right here

This is not sponsored, but check out the below walkthrough of Indyx’s 9/14 product update to visualize what I’m excited about. There’s a long road ahead until these are widely used, but I can see a world in which a digital wardrobe app becomes the foundation for all the other sustainability tech solutions above (rental, resale, styling, DPPs) while curbing the essential production problem. Better for consumers and ultimately better for the industry.

In the meantime, here’s some great advice I found on TikTok (can’t believe I just said that) — we should starting shopping for clothes the way we shop for ingredients; buy the pieces you can cook a few dishes with. *chef’s kiss*